J.R.R. Tolkien spent a lifetime crafting his tales of Middle-earth. He began work on the stories that would become The Silmarillion during World War I, while he was in his early 20s. And he was still developing his mythology even in the final years of his life, as he approached 80.

And work on Middle-earth continued after Tolkien’s lifetime. When he died in 1973, the literary mantle passed to Tolkien’s youngest son Christopher, who spent 45 years bringing more than 20 volumes of his father’s writings to posthumous publication. The latest of these, The Fall of Gondolin, was published in 2018, less than two years before Christopher’s death at 95.

This “second lifetime” dedicated to Middle-earth was a quiet one. Christopher’s scholarly and editorial approach always gave the sense of someone working faithfully in the background and out of the limelight. On the cover of the posthumous works he published on behalf of his father, Christopher’s name is dwarfed by his dad’s, and he was never listed as author or co-author, only as editor. The fact that he seldom gave interviews or made public appearances only added to this sense of Christopher as a humble steward, suggesting he only ever intended to elevate his father’s creation, rather than create anything himself.

The Great Tales Never End gives us insight into Christopher Tolkien

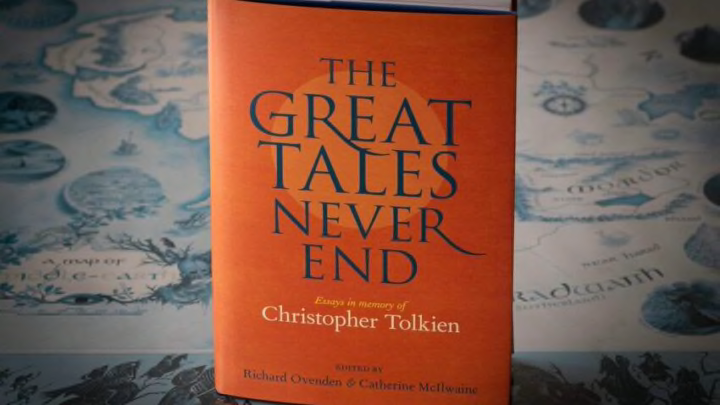

Now, Tolkien fans have a new essay collection published in Christopher’s memory that shines a light on his unique and powerful impact on the Middle-earth legendarium. The contributors to the collection, entitled The Great Tales Never End, include some of the best-known names in Tolkien scholarship, from John Garth, author of Tolkien and the Great War; to Tom Shippey, author of The Road to Middle-earth.

The collection starts on a personal note with a series of biographical sketches. The first of these, by co-editor Catherine McIlwaine, provides an overview of Christopher’s life. While it reveals few details that were not already known (drawing largely from The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien) it elegantly gathers together our existing knowledge and provides one of the most complete biographies of Christopher Tolkien in print.

What is new is the selection of images that accompany this piece. Not only do we have some photographs of Christopher that we have never seen before, but also a rather amusing reproduction of the invitation to Christopher’s 21st birthday party. Sent by J.R.R. Tolkien and his wife Edith, the card promises “Carriages at midnight. Ambulances at 2 a.m. Wheelbarrows at 5 a.m.”

The next piece, a poem composed by Christopher’s close friend Maxime H. Pascal and read as the eulogy at his funeral, is very personal. Originally delivered in French, the English translation is provided by Christopher’s widow Baillie Tolkien, another personal touch. This piece also features a particularly fascinating photograph showing a page from one of Christopher’s “botanical notebooks,” which he “kept meticulously throughout his life” to record the plants he observed through the seasons.

The poem reveals a few interesting personal details about Christopher. We learn that he “deplored the trajectory of the westernized world and […] the domination of the machine,” perhaps mirroring his father, who wove the theme of industrialization into The Lord of the Rings. In contrast to this pessimism, we also learn that “marvelous” was the adjective Christopher “use[d] most often.” While these details are interesting, their fragmented delivery in the form of poetry enables us to gain only some abstract insight into the character of Christopher Tolkien.

The final biographical sketch in the collection, a personal memory from Christopher’s sister Priscilla, who died earlier this year, sheds only a little more light on Christopher’s life and character. Like the preceding poem, Priscilla’s contribution provides us with fragments. We learn more about Christopher’s love of nature and how “observing a hawk moth basking in the sun” helped him to “cope with beauty of the world.” We have a short recap of an “extremely dramatic event” in which Christopher and Priscilla witnessed a fatal plane crash during a World War II training exercise. And we are treated to the image of a young Christopher reciting passages from John Milton’s Paradise Lost from the top of the Tolkien family garden. But Priscilla’s contribution is much too brief, totaling barely two pages of text, to provide readers with any new and substantial information on Christopher’s life and legacy.

The Great Tales Never End helps expand our understanding of Christopher Tolkien

After this biographical introduction, the collection moves into more academic territory, with a series of essays on J.R.R. Tolkien’s works and Christopher’s influence and stewardship of the Middle-earth legendarium. The first of these essays is one of the most successful pieces in the collection. Author Vincent Ferré argues that Christopher Tolkien should be considered not just as a “critic and editor,” but as a “writer of fiction.” He points out that “parts of The Silmarillion are not by J.R.R. Tolkien but by Christopher,” which was needed to “fill the gaps” left by Tolkien. Likewise, Ferré recasts Christopher’s 12-volume History of Middle-earth — which painstakingly analyses six decades of Tolkien’s writings — as “a biography of a literary work” rather than simply a piece of academic commentary. Ferré argues that “the stylistic qualities of [Christopher’s] prose” have literary value in their own right, bringing his work a little further into the spotlight he so often avoided in deference to his father.

Equally successful is Carl F. Hostetter’s essay, which gives readers an insider’s glimpse into Christopher’s process working with the Tolkien manuscripts. Hostetter is uniquely placed to write on this subject, having gone through the process himself while editing last year’s The Nature of Middle-earth, a volume that has been described as a final, unofficial entry in the History of Middle-earth series. Hostetter begins his essay by stating that “it is easy to fail fully to appreciate just how enormous an achievement” Christopher’s diligent study of the Tolkien manuscripts was. Hostetter explains the sheer volume of the Tolkien papers and how Christopher often had to interpret multiple drafts written on top of each other, all in Tolkien’s extremely difficult-to-decipher handwriting. Hostetter also reproduces images of four unpublished Tolkien manuscripts, using these to lead readers through the process of constructing a final text suitable for publication.

The other essays in the collection are more variable, both in terms of subject and quality. They will appeal to different readers depending on their different tastes and interests, but all seem to fit only loosely within the theme of the book. For instance, Stuart D. Lee’s essay is one of the book’s most interesting pieces, uncovering the story of the first radio adaptation of The Lord of the Rings, which has since been lost. But the essay does not mention Christopher Tolkien even once. Nor does Brian Sibley’s essay, which concludes the collection.

This essay collection was conceived before Christopher’s death. As co-editor Catherine McIlwaine explains, the original concept for the book was to collect a series of essays that “Christopher himself would enjoy reading.” This may explain the variation in subject matter and the absence of Christopher in some essays. But with so many Tolkien books already out there, one wonders if this might not have been an opportunity to do something different, to lean fully into the concept and produce a book entirely about Christopher.

Even if it doesn’t do its subject full justice, The Great Tales Never End nonetheless remains a loving and respectful tribute to Christopher Tolkien. And it may be the first time Christopher has ever usurped his father on the cover of a published book, bringing him ever so slightly more into the limelight that he deserves some share of.

Tolkien fans will enjoy this collection, particularly those who have delved deeper into the Middle-earth legendarium uncovered by Christopher Tolkien. But in the fullness of time, many will likely hope for something more substantial, such as a Christopher Tolkien biography or book of letters, like those produced by Humphrey Carpenter after J.R.R. Tolkien’s death. Only then will we be able to fully appreciate and understand the “second lifetime” that helped bring Middle-earth to life.

To stay up to date on everything fantasy, science fiction, and WiC, follow our all-encompassing Facebook page and sign up for our exclusive newsletter.

Get HBO, Starz, Showtime and MORE for FREE with a no-risk, 7-day free trial of Amazon Channels