Image: Sebastian Kriticos

For readers who picked up The Lord of the Rings during J.R.R. Tolkien’s lifetime, it must have been clear that there was an entire world and history behind the story of Frodo and his Ring. Brief references to historical figures, such as Beren One-hand, and distant lands, such as the lost city of Valimar, lent an authenticity to Tolkien’s world. But how these countless details related to each other, and to the broader history of Middle-earth, remained a mystery.

It was in this context that one young reader, Robert Foster, began the painstaking work of compiling all references to names, places and events in The Lord of the Rings, as well as in the two other books in Tolkien’s legendarium – The Hobbit and the slim poetry collection The Adventures of Tom Bombadil. For several years, he wrote short glossary articles on the references he compiled, which were published in fanzines. Then, in 1971, the entirety of his efforts were collected in a single book called A Guide to Middle-earth. Foster was just 22 years old at the time.

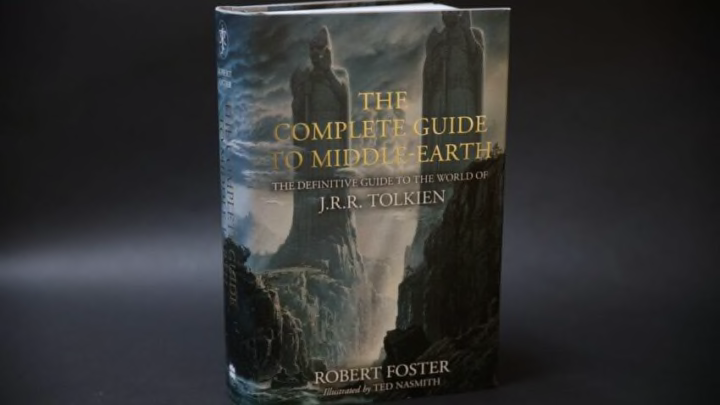

After Tolkien’s death in 1973, Foster conducted a substantial update of his A-Z guide based on the wealth of information uncovered by the posthumous release of The Silmarillion. This updated edition, published in 1978, brought Foster’s work to completion, as its new title suggested: The Complete Guide to Middle-earth.

In the years since, Foster’s encyclopaedia of Middle-earth has been reprinted several times and has acquired a reputation as the definitive reference guide for J.R.R. Tolkien’s legendarium. The book has even drawn praise from Christopher Tolkien, who pointed readers towards it in his introduction to Unfinished Tales: “If I have been inadequate in explanation or unintentionally obscure, Mr Robert Foster’s Complete Guide to Middle-earth supplies, as I have found through frequent use, an admirable work of reference.”

This week, Foster’s guide is published again in a new UK edition, for the first time in almost 20 years. This long overdue reissue comes out as an illustrated hardback designed to match the style of other recent Tolkien reissues. The illustrations, as in the previous UK edition, are provided by Ted Nasmith, one of the most celebrated visual interpreters of Tolkien’s world. While the previous UK edition boasted 50 illustrations, this new version has 54. Undoubtedly these pieces, some of which are seeing print for the first time, will be a highlight for Tolkien fans.

What’s in The Complete Guide to Middle-earth?

But beyond the new format for this reissue and the handful of new illustrations, the contents of the book are much the same as in previous editions. Few, if any, revisions seem to have been made, and some minor inaccuracies from previous versions remain. For instance, Foster describes Déagol as Sméagol’s cousin, an assertion which may not be supported by the text; it is safer to say that they are simply relatives.

Likewise, Foster’s introduction and Nasmith’s note on the illustrations remain the same as in previous editions, which is clear when you read them in 2022. For instance, Foster’s introduction references “the appearance of The Silmarillion” as if it were a recent event, rather than something that occurred 45 years ago. Likewise, Nasmith’s note, which was written in 2003, mentions a fan who reached out to him “through the medium of e-mail,” as if this were some new-fangled technology.

It would have been nice to see these supplementary pieces of text updated, but this is rather a minor quibble within the context of the overall book. The more significant issue might be that Foster’s guide has never been updated to draw substantially from any of Tolkien’s works published after The Silmarillion in 1977. This could lead fans to question the whether the book was truly as “complete” as it claims to be. But it seems that this is a necessary choice on Foster’s part given the challenge of reconciling the inconsistencies among Tolkien’s writings published in posthumous editions and the even greater challenge of determining what should be considered canonical.

In his introduction Foster seems to suggest that only the ‘big three’ works within Tolkien’s legendarium can be considered truly canonical: The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings and The Silmarillion, as well as the more minor work The Adventures of Tom Bombadil. But he also complicates matters by occasionally drawing on a handful of sources outside the text, including some of Tolkien’s letters as well as the map of Middle-earth drawn by Pauline Baynes.

The Complete Guide to Middle-earth and The Rings of Power

These questions of canon are becoming even more relevant now in the context of The Rings of Power, given that this new TV adaptation will go beyond Tolkien’s writings to introduce new characters and events. And the timing of this reissue is clearly no coincidence, coming one day before The Rings of Power premiere.

However, while one might sneer at the opportunistic nature of re-releasing this book in conjunction with the premiere of a blockbuster TV show, it is far from a shameless cash grab. Foster’s book clearly complements the new series and will be of genuine use to viewers navigating their way through a show that will undoubtedly be dense with references. And irrespective of The Rings of Power, Foster’s book is one that was long overdue for a reprint anyway.

Indeed, The Complete Guide to Middle-earth is one of the most indispensable works of Tolkien scholarship. But more than that, it is also a book that Tolkien fans will simply enjoy reading, whether that be straight through from A-Z or in a more meandering manner. Foster’s occasional interjections of pithy humor help go down easy and undercut what could otherwise be a dry tome. For instance, his comment that “Radagast does not seem to have done very much” will strike many as amusing and accurate. Even more withering is his verdict on Galadriel’s husband: “Although Celeborn was an Elven-lord of great fame and was called Celeborn the Wise, in The Lord of the Rings he does not seem especially bright.”

But the greatest literary quality of Foster’s book is simply that it gives us a sense of the enormous scale of Tolkien’s creation, perhaps more so than any other book. To leaf through thousands upon thousands of entries of names, places and events gives readers a fresh perspective and appreciation for Tolkien’s achievement, even more impressive considering that material from Unfinished Tales, the 12-volume History of Middle-earth, and last year’s The Nature of Middle-earth is not included.

While the enormity of Tolkien’s efforts is made apparent by reading through The Complete Guide to Middle-earth, Foster’s achievement is almost equally impressive. To have compiled such a work today would be remarkable enough. But Foster assembled his guide before Tolkien scholarship was a serious pursuit, in an era without personal computers or online, crowd-sourced Tolkien-based encyclopaedias.

In his introduction, Foster describes his book as the culmination of “ten years of intermittent labour.” Whether Tolkien fans have a previous edition of Foster’s guide or are coming to it for the first time with this reissue, they will agree that this was labor well spent. And after all these years, it remains the definitive guide to Tolkien’s world.

To stay up to date on everything fantasy, science fiction, and WiC, follow our all-encompassing Facebook page and sign up for our exclusive newsletter.

Get HBO, Starz, Showtime and MORE for FREE with a no-risk, 7-day free trial of Amazon Channels