It’s 2001. Friends is the most popular show on television. Apple launches a strange little mp3 player called an iPod. A new online database called Wikipedia begins to sweep tech-savvy communities of contributors. Britney Spears and Justin Timberlake have just started dating. The Spice Girls break up. Shrek and the first Lord of the Rings movie drop in theaters, creating new fandoms and revitalizing others. However, the film that steals the show is Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone, which breaks the record for the highest-grossing opening weekend of all time. J.K. Rowling is in the middle of writing and releasing her staggeringly famous series, having just put out Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire (book four) in the year 2000. She’s not yet known for her transphobia and close-mindedness. It’s the Harry Potter golden age, and somebody at the up-and-coming toy and game maker Wizards of the Coast has a bright idea: why not make a collectible card game?

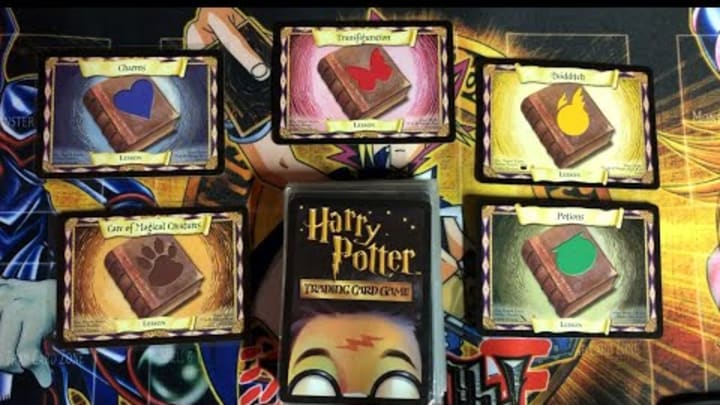

The base set of Harry Potter Trading Card Game (HPTCG) cards was introduced in August 2001 to capitalize on the Harry Potter mania that was sweeping the world ahead of the series’ first cinematic release. Following the 116-card base set, four expansions were introduced over the following two years. After releasing the game’s last set in 2003, Wizards of the Coast discontinued making HPTCG cards. In total, 641 unique cards were printed. Most of them are based on characters, objects, and events that appear in The Sorcerer’s Stone (book one). However, the last expansion included references to Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets (book two).

HPTCG was an odd little game with a set of cards that barely covers the first fourth of the Harry Potter series. It plays a little bit like Magic: The Gathering, Wizards of the Coast’s extremely famous trading card game that persists to this day as a fan and business favorite. Yet HPTCG is a lot simpler, and oriented around a franchise that was having its marquee moment when I was just 2 years old.

And while Harry Potter books and movies would continue to define childhoods as I grew up, they were never quite able to recapture the magic of the early 2000s moment when HPTCG burned bright and flared out like a bottled meteor. In spite of its cult following, Harry Potter cards would never come close to competing with the success of other trading card games like Yu-Gi-Oh!, Pokémon, and Magic: The Gathering as Wizards of the Coast had once hoped. In fact, by 2005 it would be forgotten by the vast majority of people, even die-hard Harry Potter fans. After all, they had books and movies and merchandise galore. Why would they bother with a dinky little half-finished trading card game? And how did I end up falling in love with it over 10 years later?

To answer that question, I’ll have to transport you to another moment in time: the summer of 2013. I’m 14 years old and attending a hobby camp for nerds. Activities varied, but the one thing that united that camp, which was called KidRealm, was its collective love and adoption of HPTCG.

At KidRealm, I took Harry Potter cards for granted. They were as normal as lunchtime, afternoon pickup at the roundabout, and the “camp championship” trophies that were so coveted by campers and counselors alike. HPTCG packs could be bought at the little camp shop that seemed to always appear on its jolly little rolling cart right when you needed it. They were drafted and played by nearly everyone who participated in camp. It was very common to see people hunched over card binders, reworking their decks with their friends. At KidRealm, HPTCG was ubiquitous, and I quickly became enthralled.

We were having our own little early 2000s moment without actually knowing it. And what was the harm? So what if I wanted to spend my allowance (and then some) at camp? A seemingly endless amount of smiling faces and new competitors made the experience feel rich and rewarding, at least for the week or two that I was at camp that year and the years following. We were a convent of converted gamers putting their parents' money toward trading cards that hadn’t been in print since 2003. And all this can be attributed to the business acumen of the camp’s founder: Rob Ramirez-Thompson.

The strange history of KidRealm and the Harry Potter Trading Card Game

Ramirez-Thompson founded KidRealm at the turn of the century after retiring from his job as a PE teacher. Running the summer camp started out as an experimental learning process. What kept kids coming back? What was the demographic he wanted to cater to? And how could he keep things fun and lucrative?

The camp’s adoption of HPTCG as its flagship game helped answer these questions. What kept kids coming back was a culture of gaming with their friends that could only really be fulfilled by a competitive camp environment. What demographic could be catered to in a sustainable fashion? Nerdy kids who liked to collect and compete. How to keep things fun and lucrative? Work HPTCG into the lore of KidRealm at large and use its thrall to hook new generations of campers. First, this looked like buying starter and booster decks wholesale and selling them for profit for the few years that the game was in print (that was tacked onto the price of admission for each camper to attend KidRealm in the first place). Then, it mutated into competitions in different formats, very similar to those we see from Magic: The Gathering today, if a lot more primitive. KidRealm had deck-drafting and doubles play. They had standard tournaments and counselor competitions. And all of these came complete with special shirts, trophies, and rewards reserved exclusively for those who could rise to the top.

Ramirez-Thompson’s savvy showed through most clearly, however, after HPTCG was discontinued in 2003. While another summer camp director might have seen the dying of their most lucrative activity as a disastrous development for their business, Ramirez-Thompson saw an opportunity, and that opportunity was to become the only living HPTCG distributor left standing So, he bought up all the stock he could. He bought sealed packs that would last for over 10 years, as evidenced by the fact that I was buying them in 2013 as if they were fresh off the shelves. At that time, KidRealm was still playing, still standing on the shoulders of a collectible card game that had been defunct for over a decade. And though it would eventually pivot to another game called Castle Combat – this one designed by none other than Ramirez-Thompson himself in order to cut out the middleman and increase profit margins on every card pack sold – the camp’s ability to milk HPTCG for all it was worth (literally) led to a cocktail of emotions within entire generations of campers that I feel conflicted about to this day.

A childhood love of trading card games feels joyous on its surface. There’s nothing better than tearing open a shiny new pack of cards and building a synergized deck with the gems you find within. However, as I’ve grown into myself as a writer and adult, the dark side of hobbies like this has shown itself plain.

Harry Potter, Magic: The Gathering, innocence, commerce and you

One must look no further than Magic: The Gathering (MtG) to see what I’m talking about. Indeed, MtG represents a case study in what HPTCG could look like today if it was successful and not tied to a flagging external IP. MtG is Wizards’ most lucrative franchise by far. They release more new sets of limited-run cards that collaborate with other popular franchises, like Marvel and Monty Python, than it is possible to keep up with. The value of these cards is purely based on their established fandoms, which will stop at nothing to get their hands on the newest merch. Meanwhile, new core sets of the game drop each year at a rates that – at this point – seemed chosen to milk as much money as they can from players who want to stay up to date with the newest trends. In fact, Wizards recently released its 2025 schedule for Magic, which features a whopping six distinct card sets.

What’s more, MtG has expanded into the sphere of online play with MtG: Arena, which was first released in 2018 but has since risen to the very top of Wizards’ priority list. The reason? microtransactions. It’s never been easier for Wizards of The Coast to extract money from its players as they attempt to keep up with the staggering pace of MtG releases. It’s no wonder that the company has chosen to steadily move the majority of its competitions online, uploading them to MtG: Arena’s interface and thus making the virtual experience a must-have for competitive and non-competitive players alike.

As a games and culture journalist, it’s my job to investigate the way play makes us feel. Interrogating specific games can be a slippery slope since, as we’ve seen in this piece alone, much of the industry creating these kinds of experiences sees their consumers as set quantities who are to be separated from their money over a time scale tuned to quarterly earnings reports. However, if there’s one thing I can be thankful for, it’s the innocent feeling of tearing open a pack of HPTCG cards with my friends when I was 14, light streaming through the window and the smell of summer pouring in from the cafeteria’s opened door.

While strategizing among like-minded players, the possibilities felt endless. And though all things will eventually go out of print, succumbing to the ever-present thrum of the materialistic desires that spawned their development in the first place, there’s nothing quite like the innocence of believing that what’s in front of us was made solely to entertain. That the money, time, and creativity put into a product serves only to enhance the user experience. That the end goal is joy.

To Rob Ramirez-Thompson, to Wizards of the Coast and their incorporating company Hasbro, and to trading card game makers everywhere: what we need today is more of that magic, rather than the MtG-esque kind you’re peddling. And while I have you to thank for so much joy over the years, I will never stop encouraging readers and fellow gamers alike to sever the unseen hands reaching into their pockets at the wrist. Pursuing the kind of fun that can be sustainable for both our mental health and our wallets will always be a just pursuit.

Now all that’s left to do is go forth and enjoy responsibly.

To stay up to date on everything fantasy, science fiction, and WiC, follow our all-encompassing Facebook page and Twitter account, sign up for our exclusive newsletter and check out our YouTube channel.